For more than a decade, Munising’s Elm Avenue and City Dock have doubled as an outdoor art gallery where light poles become frames and the streets tell stories through local creativity.

Thanks to the Munising Downtown Development Authority’s Banner Art Contest, these public spaces are once again brightened by the work of community artists, celebrating the spirit and scenery of the Upper Peninsula.

Held every two to three years, the banner contest continues to evolve as one of the DDA’s signature public art initiatives. The 2025 installment invited submissions under the theme “The Four Seasons of Munising,” prompting artists of all ages to express their connection to the region through depictions of spring blooms, summer sunsets, autumn trails and icy winter shores.

This year’s contest drew 85 submissions from residents across Alger County, ranging from young children to seasoned creatives, underscoring the contest’s inclusive approach.

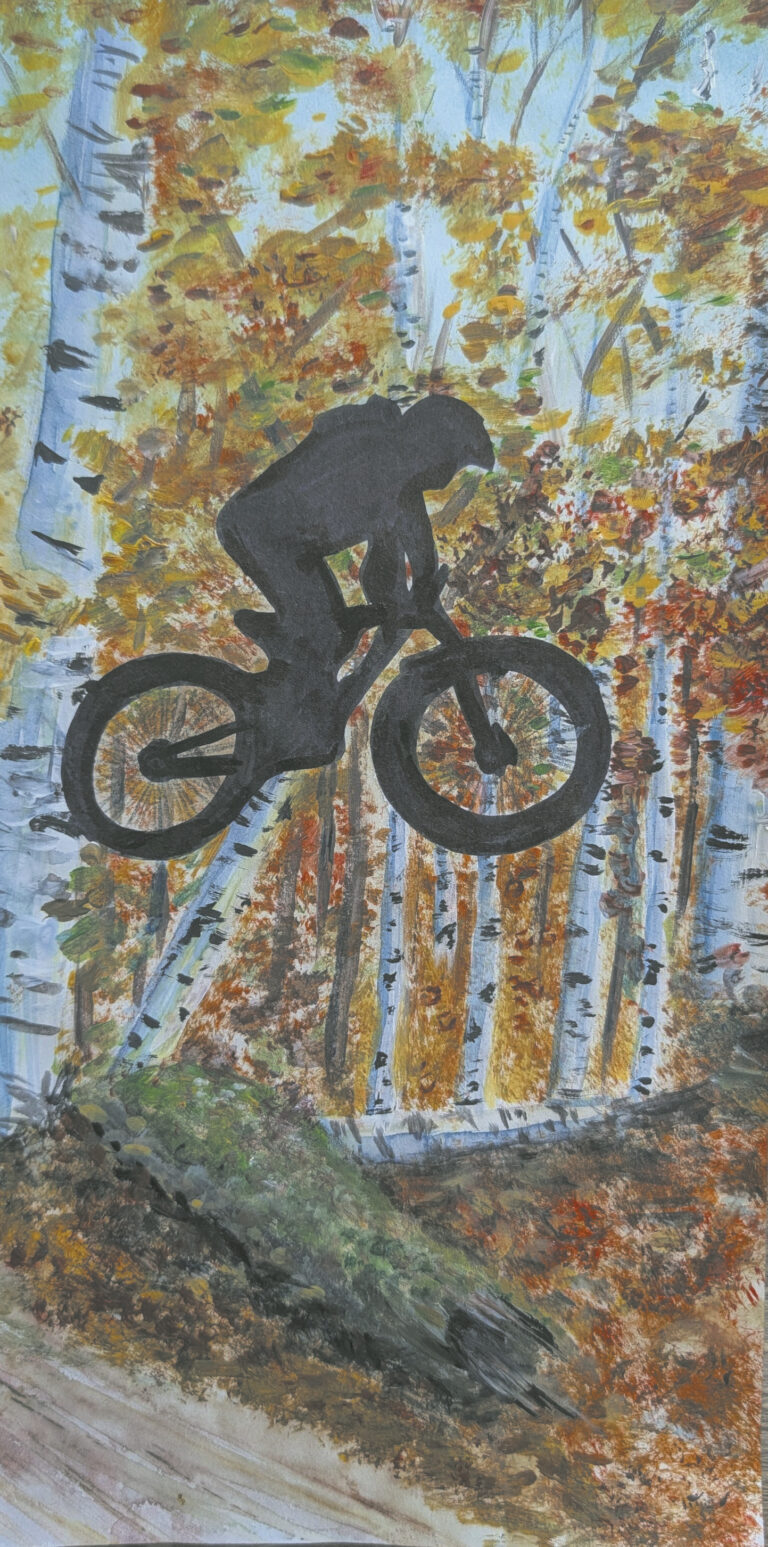

The top 10 winning entries now adorn streetlight banners downtown, with the top four also receiving cash prizes. The winning artists are: 1. Kristen Sontag-Long: “Mountain Bike” 2. Connor Nelson: “East Channel Lighthouse” 3. Jack Nelson: “Coastline with Swirly Clouds” 4. Hazelynn Winsor: “Loon” 5. Layla Gould: “Snowman Welcome” 6. (tie) Emily Laufenberg: “Eagle & Kayaker” 6. (tie) Kristen Sontag-Long: “Ice Climber” 8. Madeline Cole: “East Channel Out a Window” 9. Matthew Nord: “The Bermuda” 10. Tamryn Nolan: “Ice Cave” Sontag-Long, who earned two winning spots, has become a familiar name in the contest’s history. Her “Mountain Bike” piece, a nod to Munising’s fast-growing reputation as a trail-riding destination, stood out not just for its dynamic composition but for reflecting a segment of local recreation that’s gaining momentum year after year.

According to Kathy Reynolds, longtime DDA director, the idea for the banner contest first came after seeing children’s art banners displayed in a small downstate town. That inspiration sparked a local experiment more than a decade ago, and it has since grown into one of Munising’s most visible community art efforts.

“We wanted to create something that wasn’t just decorative, but meaningful,” Reynolds said. “The banners pull people through town, connect the dock to the downtown and tell stories along the way.”

The value of projects like these goes far beyond aesthetics. Studies from organizations such as Americans for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts affirm that public art is a catalyst for economic and civic vitality.

Not only does it create welcoming, visually engaging places, but it also increases foot traffic to small businesses, enhances tourism experiences and promotes a sense of local identity.

In Munising, the contest achieves all of this and more.

“We see people coming into our office, or stopping on the street, to ask about the art,” Reynolds said. “We even have other towns reaching out, asking how they can start something similar.”

While the banners brighten the town for visitors, their greatest impact may be on the residents themselves, particularly the young artists who see their work printed larger than life and displayed for all to admire.

“We’ve had submissions from second graders to seniors,” Reynolds said. “The kids especially light up when they see their work hanging up. Their families come down, take pictures — it’s a big deal.”

Most artists gravitate toward familiar landmarks: Pictured Rocks, the East Channel Lighthouse, Grand Island. But each contest brings unexpected interpretations too.

This year’s entries included a shipwreck tribute to The Bermuda, a view through a windowpane and a moody shoreline under stormy skies. The diversity of submissions reveals how differently people experience the same place.

And that’s the point, Reynolds said.

“It’s not just about showing what’s famous. It’s about expressing what feels meaningful,” she said. “Sometimes that’s a landscape. Sometimes it’s a memory or a fish or a snowman.”

Reynolds recalls a previous year when an artist submitted an image of a woman quietly fishing off a dock.

“That banner didn’t show a landmark, but it captured something authentic about life here,” she said. “That’s what makes these pieces special.”

The banners themselves are printed using weather-resistant materials specially tested to survive Munising’s wind tunnels and brutal winters. The city uses color-coded banners to indicate their placement — blue for Elm Street, green for Superior and yellowish hues for M-28 — making it easy for city crews to hang and rotate them efficiently.

“They last about two to three years, sometimes longer,” Reynolds said. “We rotate contests as needed, depending on how well they hold up.”

The banner contest is part of a broader push by the DDA to reimagine Munising’s public spaces.

Over the past decade, the city has added art installations, bike racks, benches, flower beds, upgraded trash receptacles and Art in the Alley, a display of individual paintings exhibited along one of downtown’s most popular pedestrian walkways.

These efforts work in tandem to draw visitors off the water and into downtown shops and restaurants.

“It’s all about walkability,” Reynolds said. “If you can get someone to walk down a street, they’re more likely to walk into a business. And if the town looks good — if it has personality — they want to come back.”

Foot traffic, she said, has increased dramatically in the last 10 to 15 years. Though aided by major projects like the M-28 improvement and new sidewalks, Reynolds credits much of that success to how downtown feels — a combination of intentional design, public art and civic pride.

“People want to be in a place that feels cared for,” she said. “That’s what we’re working toward every time we do something like this.”

Perhaps the most telling aspect of the program’s success is how the community embraces it. The banners, and in fact all of the public art, have become a source of shared pride, respected and protected by residents.

“People respect it. They protect it,” Reynolds said. “If something ever did happen, I think there’d be a real outcry.”

The banners may hang on city poles, but they belong to everyone who walks by and sees a piece of themselves, or their hometown, reflected in the artwork.