There was no doubt that the community wanted to see the Munising Mustangs win the state championship. But how could fans watch? Well, according to 100,000 spambots on Facebook, it was as simple as clicking a link.

According to data compiled by The Munising Beacon, almost a quarter million Facebook posts, comments and interactions provided links to fraudulent broadcast posts from Munising’s regional championship on March 15 to the state championship on March 25.

“During the tournament and the games leading up to it, the amount of spam on any given day was astonishing. As the team advanced, it got progressively worse and by the end I was blocking, declining and removing hundreds of spam posts,” said Cori-Ann Cearley, a local business owner and one of the moderators for the Munising Informed Facebook page. “I wanted the people who might not be as tech-savvy as others to not be taken advantage of. I was concerned someone from our community would click on a spam link and have the memory of what these kids accomplished spoiled by some form of identity theft or worse.”

The range of these spambots was wide, interacting with whatever mom-and-pop shop, non-profit organizations or church that celebrated the Mustangs.

These posts weren’t just annoying. They were bad for business. According to Jaymie Depew, a social media specialist and content creator for the Alger County Chamber of Commerce and the Munising Visitors Bureau, spam posts can be misleading for many of the small business owners and volunteers running social media pages.

“I shared two posts about the Mustangs regional and state wins on the Alger County Chamber of Commerce’s Facebook page and spammers wasted no time sharing unsolicited messages, most of which consisted of false links alleging where fans could watch the game. We saw this across the board regarding local businesses. Many had a difficult time keeping up with deleting them in a quick fashion because there were so many, and unless social media is your only job, it’s near impossible,” she said.

Spambots did not limit their attacks to just Munising. Frankfort, a similarly sized coastal town in the other Division 4 semifinal saw the same spam, as well as every team in the tournament. According to Bill Vajda, the incoming director of the Upper Peninsula Cyber Institute at Northern Michigan University, any chance to get a click can mean money for spambot owners in pay-per-click advertising. Learning an internet user’s browsing habits can also be profitable by selling that data to third-party advertisers.

“Let’s say you’re using Facebook and your mouse cursor is hovering over different parts of the page than others. It’s tracking that. It’s tracking that you spent more time over a Munising sports issue than potato recipes or whatever other interests you may have and it’s calculating that every microsecond,” he said. “It’s amalgamating that into a profile for what you’re doing and everyone with an interest in what you’re doing, there are bots waiting. It might be spam for you, but it’s a bot posting a comment to make you aware of something you would want to check out.”

Some spambot links direct to foreign websites or to shops while others can link to more malicious locations. Of the links investigated by The Munising Beacon, some websites provided a game broadcast feed that violated United States broadcasting laws and regulations by pirating and reproducing the feed. Others required users to click extra boxes that could initiate malware downloads.

In the future, the MHSAA has been working to clarify what streams are real and which streams are fake. The state’s high school athletic governing body works primarily with the NFHS Network to provide video streams, which usually do not have commentary and are operated by autonomous cameras. A couple individual companies across the state will provide video streaming for specific schools, like M123/EUP Sports Network out of Newberry. However, MHSAA officials say it is a point of education often before and during the season.

“We deal with this topic during New (Athletic Director) Orientation every fall – teaching them how to create their own post with a link instead of sharing a potentially dangerous link,” said Jon Ross, MHSAA Director of Broadcast Properties. “When we see a school has re-tweeted or shared a spam post, we contact them to take it down and explain how to spot these posts going forward. And we post on our social accounts when playoffs are starting to be aware of these spam links. If a fan/viewer has a question on a link, we encourage them to go directly to NFHSNetwork.com and search for their game that way, instead of clicking a link.”

Vajda said that there are millions of spambots purveyors worldwide with different rules and regulations in each country. Understanding where the link goes when clicked is important for internet safety, he said.

“Anything you click on a computer, you either have to have some underlying trust that it is what it is, or you run that risk,” Vajda said.

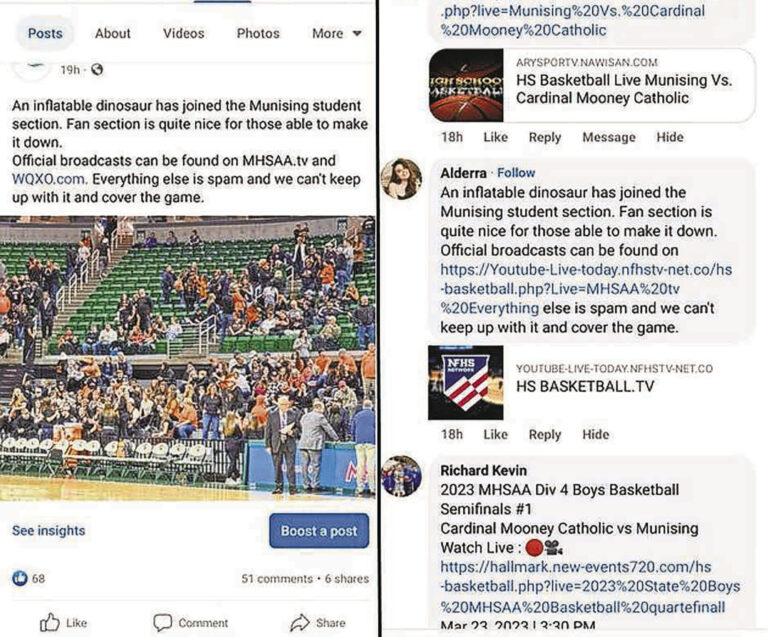

The Munising Beacon was the only Facebook page to report on a student wearing an inflatable dinosaur costume to the MHSAA Division 4 semifinals (left), but a bot was able to copy the words of the post and replace the link in a way that would be harmful and misleading to casual fans online (right).