Where do birds go when they migrate?

If you were to ask that question in the late 17th century, you might have been told that birds migrate to the moon.

We’ve come a long way since then when it comes to understanding migration, and new technology is allowing us to have an even better understanding of the phenomena.

Knowing where, how and when birds, bats and other creatures migrate tells us about our ecosystem and its overall health. Identifying stopover habitat where migratory wildlife rest and refuel, tracking population numbers and measuring the impact climate change has on wildlife are just some of the ways that migration data can help us understand more about our environment and how we can conserve and protect it.

Because of Michigan’s geography, the Straits of Mackinac offer a unique opportunity to observe migration between two peninsulas, and it is something that we have only recently begun to study.

The data gathered there has the potential to revolutionize our understanding of migratory animals and can be used in conservation efforts throughout the Western Hemisphere, which is why researchers, educators and government agencies like the Michigan Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Forest Service have come together to study the area.

Origins of migration research Migration research is a relatively new field, with American researchers beginning to delve into it in the early 1900s through the coordination of nationwide bird banding programs.

At a cost of less than a dollar each, the metal leg bands are inexpensive, but the method has a limitation: They are tiny. While the size is safer for the bird, the bands can be difficult to read from a distance, and the recovery of banded birds is a game of chance at best.

In the 1970s, researchers began repurposing satellite transmitters to track bird migration. While the data gathered from these devices is far more accurate and detailed than banding data, the transmitters are not cost-effective, with a tracking system for a bald eagle costing upwards of $5,000. For a well-designed study with multiple subjects, this can add up quickly and can be difficult to fund long-term.

The new age of research

Researchers needed a way to track wildlife that could provide the detailed analytics of satellite transmitters but still retain the cost-effectiveness of banding and be as safe as possible for wildlife.

This led to the creation of the Motus Wildlife Tracking System, an international research network that uses automated radio telemetry to track wildlife. (Motus is Latin for movement or motion.)

“The Motus Wildlife Tracking System is an international collaborative research network that uses cooperative automated radio telemetry to track small flying organisms (birds, bats and insects),” the system website reads. “When compared to other technologies, automated radio telemetry currently allows researchers to track some of the smallest animals possible, with high temporal and geographic precision, over great distances.

“The system enables a community of researchers, educators, organizations and citizens to undertake impactful, cost-effective research and education on the ecology and conservation of migratory animals.”

Built on existing antenna towers, new pop-up towers or rooftops, the Motus antennas are equal parts cost-effective and efficient. Each Motus tower tracks migratory wildlife by receiving signals from within an 11-mile radius of the tower.

Every time one of the tracking tags enters the tower’s range, the information is uploaded to the Motus Wildlife Tracking System’s online database.

The tags that the antennas track are lightweight and can be used to study species as small as warblers and dragonflies. Over 250 species are currently documented in the ever-growing database, and community scientists, researchers, educators and government agencies can access the data for free to view findings from throughout the world.

Thirty-four countries are currently involved in the Motus tower research, and there are just over 2,000 stations operating worldwide.

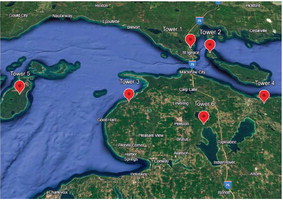

Motus research in Michigan To date, 40 Motus towers are scattered across Michigan. Because of their small size, the antennas can be built almost anywhere that allows them to receive a clear signal, with some being built on military bases and college campuses, in remote wildlife areas and even at farmers markets.

Most of the antennas in the Lower Peninsula of Michigan were built through the support of Audubon Great Lakes, Kalamazoo Nature Center, the Smithsonian Institution and Detroit Zoo. They form a line from Detroit west to Kalamazoo, with an outlying cluster built near the Grayling area to specifically study the once-endangered Kirtland’s warbler.

Currently, four of the state’s antennas are on properties managed by the Michigan DNR, with three more being built at Cheboygan State Park, Wilderness State Park and the DNR’s property on Mackinac Island.

Spearheading the building effort in this area is Mackinac Straits Raptor Watch, a nonprofit organization that has monitored the migration of raptors, songbirds and waterfowl in the Straits region since the 1980s.

Watch partners on the project include the DNR, the U.S. Forest Service, the University of Michigan and Central Michigan University, with funding provided from grants and private donors.

Each partner is allowing Raptor Watch to build an antenna on its property, with the DNR allowing antennas at three separate locations. Once completed, the series of six towers will offer the clearest picture to date of how wildlife migrates throughout the Straits region.

Because of the region’s unique geography, birds funnel through the Mackinac Straits to avoid the need to cross wider expanses of Great Lakes water.

Raptor Watch’s migration count sites have set nationwide records for the number of red-tailed hawks and the most golden eagles seen east of the Mississippi.

Birds typically not seen in Michigan, like black vultures, Swainson’s hawks and American white pelicans, have even been detected at the Straits.